Situation of Clean Air Rooms and Air Purifiers in Thailand

Thailand continues to experience persistent fine particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less (PM2.5), posing significant risks to public health, particularly among vulnerable populations. About 13.6 million Thai children are exposed to unsafe PM 2.5 levels each year (1). During high pollution period, many child development centers and schools are temporarily closed due to poor air quality. This ongoing environmental challenge has driven widespread adoption of clean air rooms and air purifiers in homes, schools, hospitals, and other public facilities. Clean air rooms function as both preventive and mitigative health interventions by reducing exposure to harmful airborne particles. National and local authorities, including the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), and the National Health Security Office (NHSO), have implemented targeted initiatives to expand access to such facilities. The MoPH has set a strategic target to provide at least one clean air room in every district nationwide (2). Between June and August 2023, air quality assessments conducted at 20 early childhood centers in Bangkok indicated that 35.6% of children remained indoors for more than 9.5 hours per day. Among these children, 59.4% slept in air-conditioned rooms, whereas 38.9% did not. Only 14.6% of children’s bedrooms were equipped with air purifiers, while 83.8% lacked such devices (3, 4).

Among households that used air purifiers, 55.8% reported operating them for six to seven days per week. These centers are exposed to multiple air pollutants, including PM2.5, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), ozone, and airborne microorganisms. Environmental factors such as elevated indoor temperatures in non-air-conditioned centers and insufficient ventilation in air-conditioned centers further exacerbate health risks. The capacity of Bangkok’s early childhood development centers to protect children from PM2.5 exposure varies substantially across facilities (3, 4).

In response, the Department of Health (DOH) has issued guidelines encouraging households, public buildings, and child development centers to establish “clean air shelters”. According to a study by the DOH, clean air shelters can reduce PM2.5 concentrations by 20–70%, depending on various factors (5), similar to initiatives in London that highlight the health and co-benefits of clean air in schools (6).

For households, a 2021 study found that 78% of Bangkok residents did not have PM2.5 air purifiers (7). The DOH currently recommends creating clean rooms at home by selecting a sealed space without gaps, sealing windows and doors with tape or caulk, avoiding indoor particle-generating activities, and installing air purifiers in accordance with guidelines for households, public buildings, and child development centers (5). Recently, low-cost do-it-yourself (DIY) clean room methods have been promoted through health media and online platforms, such as adapting fans with filters, using dust-fighting mosquito nets (bed nets) (8). While these DIY solutions can be effective, the DOH notes that clean rooms perform best when equipped with air purifiers. In non-air-conditioned homes, however, sealing rooms for extended periods may lead to heat buildup. Consequently, most households use temporary clean air rooms only during peak pollution episodes and ventilate once conditions improve, following DOH recommendations.

The demand for air purifiers in Thailand has risen sharply in response to the increasing severity of annual PM2.5 pollution. Initially, the country lacked stringent product standards or regulations specific to air purifiers, leading to wide variations in product quality and performance. By 2023, the Thai air purifier market was valued at USD 121.75 million (approximately THB 4.2 billion) and is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.95% between 2024 and 2029 (10). In 2022, the Office of the Consumer Protection Board (OCPB) classified air purifiers as label-controlled products under the Consumer Protection Act, requiring manufacturers and importers to accurately disclose product specifications (11).

Concurrently, the Thai Industrial Standards Institute (TISI) introduced national standards outlining minimum safety and performance requirements for air purifiers (12). In 2025, the Central Committee on Prices of Goods and Services (Ministry of Commerce) designated air purifiers as controlled products under the Price of Goods and Services Act (13).

More recently, the Local Health Security Fund (LHSF) under NHSO has launched initiatives to mitigate air pollution impacts on young children. The program promotes community awareness, establishes Clean Air Rooms in child development centers, installs air purifiers and ventilation systems, and uses low-cost sensors to monitor indoor air quality weekly. Regular health assessments are also conducted to track children’s well-being. Pilot activities focus on high-risk northern provinces including Chiang Mai, Chiang Rai, Lamphun, Lampang, Nan, Mae Hong Son, and Phrae, with emphasis on districts such as Mae Chaem, Pai, and Chiang Dao.

Challenges of Clean Air Rooms and Air Purifiers

At present, there are no systematic government-funded programs providing free air purifiers to the public, apart from occasional donations from public agencies or private organizations to schools, child development centers, and hospitals in high-risk areas. Despite increasing public awareness of clean air rooms and air purifiers, equitable access and effective use remain limited due to several persistent challenges. Key issues and obstacles include:

- High cost and affordability: Limited budget for procurement and maintenance of quality air purifiers. Air purifiers are relatively expensive household appliances compared to the average income in Thailand. Additional long-term costs, such as electricity use and periodic filter replacement, further increase the financial burden (14). Without government subsidies or distribution programs, these expenses fall entirely on individuals. As a result, some households choose lower-cost alternatives, such as wearing masks or using simple DIY air filters, which generally provide lower efficacy. However, some centers also use DIY air purifiers with fan-mounted filters due to budget limitations, supported by community contributions or local administrative organizations (LAOs).

- Lack of information and purchasing standards: Thai consumers have historically faced difficulties in selecting air purifiers due to the absence of mandatory standards or clear performance labeling. Purchasing decisions were often based on advertisements or sales claims, some of which were exaggerated or misleading (15, 16).

- Environmental and housing constraints: Creating clean rooms is not feasible for all households. Many homes in Thailand, particularly in rural areas or those without air conditioning, are built with open ventilation to reduce heat. Modifying such spaces to be fully sealed can cause excessive indoor heat, especially in the country’s hot and humid climate. Without air conditioning, keeping windows and doors closed throughout the day is often impractical. Even in schools, many classrooms lack air conditioning, and establishing clean air classrooms requires multiple fans or air conditioners, along with air purifiers, which increases costs and maintenance needs. Consequently, the physical structure of homes and buildings poses a significant limitation to implementing clean air rooms.

- Lack of long-term policy support: Government measures on clean air rooms and air purifiers have largely been voluntary and short-term, activated primarily during periods of crisis. There is no permanent policy framework or sustained national budget allocation. For example, Bangkok’s Clean Air Classroom project is funded by the BMA through its Office of Education and Office of Social Development, along with ad hoc projects such as the provision of 1,743 portable air purifiers to BMA schools (17). No central government budget currently exists to expand similar initiatives to schools in other provinces on an annual basis. While the NHSO has recently begun offering limited support, there are still no household-level incentives such as tax deductions for air purifier purchases or other financial benefits. Consequently, access remains dependent on individual purchasing power and personal concern. To date, the government’s role has focused primarily on regulating price and quality, with few proactive incentives. However, the MOPH’s 2025 medical and public health operational plan includes the expansion of clean air rooms and dust-free bed nets in high-risk areas, with a target of at least 5,000 units (18).

- Maintenance and occupant behavior: Effective performance of air purifiers depends on proper operation and maintenance. However, some users lack awareness of essential practices or fail to follow them consistently, reducing device efficiency. Common issues include operating air purifiers with windows open or neglecting timely filter replacement, both of which significantly diminish filtration effectiveness. These challenges can be mitigated through targeted educational campaigns and user training.

- Inconsistent monitoring and data collection: LHSF guidelines encourage weekly monitoring of indoor air quality in child development centers using air quality measuring devices. However, implementation varies depending on local capacity and available resources, resulting in inconsistencies across institutions and regions.

- Unequal access: rural and remote centers often lack clean air rooms compared to urban ones.

What is a “Clean Air Room”?

The DOH classifies clean air rooms into four types, selected according to intended use, budget, and maintenance capacity (5). The official website (https://podfoon.anamai.moph.go.th/) provides a map of certified clean rooms, detailed public guidelines, and access to the DOH consultation hotline (1478) (9).

A clean air room is a designated indoor space designed to minimize PM2.5 and other pollutants, often through the use of air purifiers, in order to maintain safe indoor air quality. During periods of severe outdoor pollution, authorities frequently advise the public to remain in such rooms (19). Clean air rooms employ measures to prevent the infiltration of polluted air, filter indoor air, and avoid activities that generate indoor pollutants. The objective is to create a safe environment where PM2.5 levels are significantly lower than outdoors, thereby reducing exposure. This approach is particularly beneficial for vulnerable populations, including children, older adults, and individuals with cardiovascular or respiratory conditions.

How to Create and Maintain a PM2.5-Free Clean Air Room?

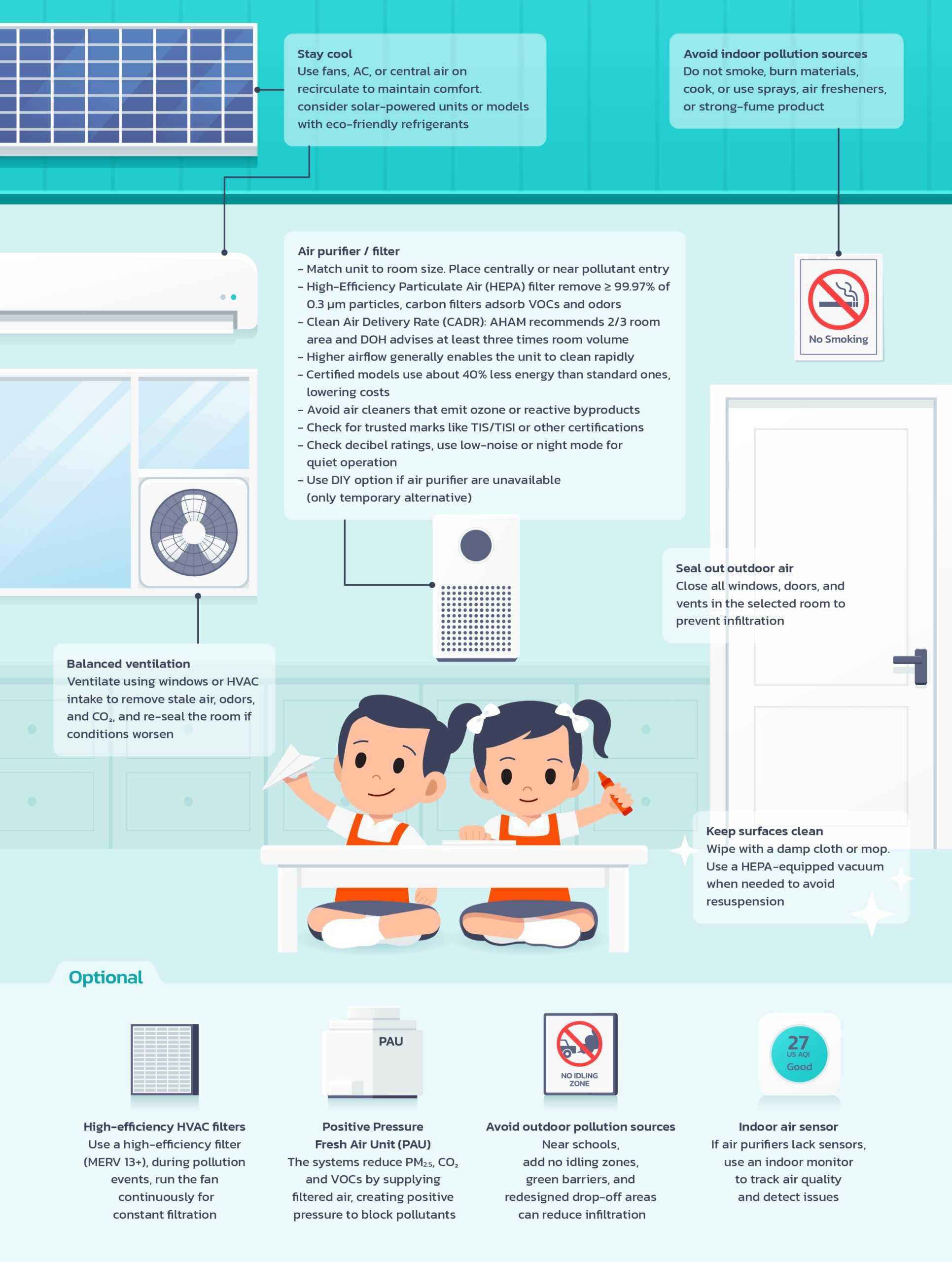

- Choose the right room: Select a room with structural characteristics that can be easily sealed and that offers a comfortable environment for extended occupancy. This helps reduce the need to open doors frequently, thereby maintaining cleaner indoor air.

- Seal out outdoor air: Close all windows, doors, and vents in the selected room to prevent infiltration of smoke or pollution. However, be mindful that inadequate ventilation over extended periods can contribute to symptoms associated with Sick Building Syndrome (SBS) (20).

- Air purifier (air cleaner) / filter:

- Size and placement: Select an air purifier that is appropriately sized for the room’s volume. Position it to maximize airflow, ideally in a central location or near potential pollutant entry points, ensuring there is space around it for unobstructed circulation. Avoid placing the unit too close to walls or corners, under an air conditioner, near a headboard, or directly in front of a bathroom.

- Filter type: A True HEPA (High-Efficiency Particulate Air) filter uses a fibrous medium capable of removing ≥ 99.97% of particles measuring 0.3 µm in diameter (21, 22), effectively targeting particulates such as PM5. To address gases and odors, an activated carbon filter can adsorb VOCs and other gaseous pollutants (23).

- CADR (Clean Air Delivery Rate): The CADR is a key indicator of an air purifier’s performance; a higher CADR reflects faster air cleaning and greater suitability for larger rooms. Select a unit with a CADR appropriate for the room size. The Association of Home Appliance Manufacturers (AHAM) recommends a CADR (in cubic feet per minute, cfm) equal to approximately two-thirds of the room’s area (in square feet) for rooms with 8-foot ceilings. The Thai Department of Health advises a CADR at least three times the room’s volume (24). CADR information can typically be found on the product packaging or in the user manual. When possible, operate the portable air purifier in the room at its highest fan setting.

- Airflow (Air Volume Flow Rate): Airflow refers to the volume of air moved by the purifier’s fan, typically measured in cubic feet per minute (CFM) or cubic meters per hour (m³/h). This metric indicates how quickly the purifier can cycle the air in a given space. Higher airflow generally enables the unit to clean larger rooms or to purify smaller rooms more rapidly (24, 25)

- Energy use: Operating an air purifier requires electricity, so it is important to consider energy consumption. Check the unit’s wattage or Energy Star rating before purchase. Energy Star–certified air cleaners are, on average, about 40% more energy-efficient than standard models, which can help reduce electricity costs (26).

- Ozone and byproducts: Avoid air cleaners or furnace/HVAC filters that generate ozone or other reactive byproducts. Some technologies, such as electrostatic precipitators, ionizers, uncoated ultraviolet (UV) lights, or plasma systems, may emit ozone, which can pose health risks (23, 27).

- Certifications, labeling, and verified marks: Refer to official lists or look for labels indicating compliance with recognized standards, such as TIS/TISI certification or marks from other trusted agencies. These labels assist consumers in comparing purifier performance. When evaluating models, keep in mind that no air purifier can remove 100% of pollutants from a room, and actual performance may vary depending on placement and usage.

- Do-it-yourself (DIY) options: If portable air cleaners are unavailable or unaffordable, a DIY air cleaner can be used as an alternative.

Note: DIY air cleaners can serve as a temporary alternative to commercial air cleaners. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommends using DIY units only when products of known performance, such as certified portable air cleaners, are unavailable or unaffordable. They are not recommended as a permanent substitute. Always follow safety guidelines when constructing and operating a DIY purifier (19).

- Balanced ventilation: When outdoor air quality improves, even temporarily, ventilate the room with fresh air by opening windows or operating the HVAC system with a fresh air intake. This helps flush out stale air, odors, and carbon dioxide buildup. Be prepared to re-seal the room if air quality conditions worsen (28).

- Stay cool: Use fans, air conditioners, or central air conditioning (AC) to maintain a comfortable indoor temperature. If the HVAC system or air conditioner has a fresh air option that draws in outdoor air, disable it, close the intake, or set the system to “recirculate” mode. To reduce environmental impact, consider using solar power to operate air conditioners and select models that use eco-friendly refrigerants, such as R-290 or R-600a (29).

- High-efficiency HVAC filters (if available): If the home is equipped with a central HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) system, install a high-efficiency filter with a Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) of 13 or higher (19). During pollution events, operate the HVAC fan continuously (“on” mode) to ensure constant air filtration. Note that not all systems can accommodate a MERV 13 filter due to increased airflow resistance; consult a qualified professional if unsure. Additionally, close the HVAC outdoor intake vent, if present, or set the system to “recirculate” mode to prevent drawing in polluted air.

- PAU (Positive Pressure Fresh Air Unit) / OAU (Outside Air Unit) (Optional): These systems help reduce PM5, carbon dioxide (CO₂), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) by supplying filtered fresh air into the room. They create positive pressure that prevents polluted air from entering, while also increasing oxygen levels and lowering CO₂ concentrations.

- Air changes per hour (ACH): ACH refers to the number of times the air in a room is replaced with fresh air in one hour. A higher ACH generally indicates better ventilation and improved air quality.

- Monitor air quality (if possible): Use an indoor air quality monitor to measure pollutant levels within the room. Monitoring can verify the effectiveness of clean air strategies, track changes over time, and alert occupants to potential issues such as open doors, worn-out filters, or air leaks.

- Noise level: Air purifiers often operate continuously, particularly in bedrooms or living areas. Review the decibel (dB) ratings at different fan speeds before purchase. For quieter operation, select models with low-noise features or a night/silent mode. Consider running the purifier on a higher setting when the room is unoccupied and switching to a lower setting during nighttime use.

- Maintain and replace filters: When selecting an air purifier, review the expected filter lifespan and the cost of replacements. Replace filters according to the manufacturer’s instructions, or more frequently during periods of heavy smoke or high pollution. Filters can accumulate large amounts of PM5 and may clog quickly, reducing airflow and efficiency. If the filter appears visibly dirty or airflow decreases, install a new one. During severe pollution episodes, replacement may be required more often than the standard interval recommended by the manufacturer.

- Address outdoor sources first: Even the best clean air room cannot fully offset high outdoor pollution ingress. Near schools, measures such as no-idling zones, green barriers, and redesigned drop-off points can help reduce indoor infiltration (28).

- Avoid indoor pollution sources: To maintain clean air, avoid smoking, burning materials, cooking (even steaming or boiling), and using aerosol sprays, air fresheners, or other products with strong fumes inside the room.

- Keep surfaces clean: Even with filtration, some particles will settle on surfaces. Regularly dust with a damp cloth or mop. Avoid vacuuming unless necessary, and only use a vacuum equipped with a HEPA filter to prevent particle resuspension.

- Spend time in the clean room: During pollution events, occupy the clean air room as much as possible, particularly for sleeping and for vulnerable individuals. Increased time in filtered air reduces overall exposure.

Additional features: Modern air purifiers often include extras like air quality sensors, auto mode (adjust fan speed based on pollution), smart connectivity, and filter life indicators. While not essential, features like PM2.5 displays or auto mode improve convenience and ensure optimal use. For institutions, commercial-grade models may offer larger coverage, quieter operation, and lockable settings. Always ensure smart features don’t distract from the purifier’s core function, filtering air effectively.

Conclusion

While the adoption of clean rooms and air purifiers has increased in Thailand, disparities in access persist between urban, higher-income populations and rural or low-income groups. The government has taken steps to address some of these challenges, such as price regulation and quality control. However, in the long term, tackling the root causes of air pollution is essential, as improving outdoor air quality would reduce reliance on costly air purification technologies. During this transitional period, when PM2.5 levels remain critically high, ensuring equitable, safe, and widespread access to clean rooms and air purifiers is an urgent public health priority.

Clean air rooms represent a practical, evidence-based intervention to protect health during high PM2.5 episodes. Selecting appropriate air purifiers and filters, ensuring balanced ventilation and regular maintenance, and implementing these measures where appropriate can help maintain both health and co-benefits. By following these guidelines, consumers can make informed choices, and policymakers can establish standards and recommendations that promote healthier indoor environments for all.

Policy Recommendation

- Certification and designation programs: Develop national programs to certify air purifiers and designate clean air rooms for use in households and public buildings. Provide “clean air room” toolkits that include True HEPA filters, educational materials, and public awareness campaigns.

- Standards and incentives: Establish technical standards and incentive programs, such as subsidies or tax credits, for the use of HEPA air purifiers, particularly in regions with frequent high PM5 episodes (30). Ensure accurate product labeling, including CADR, recommended room size, and filter specifications, to enable informed consumer choices. Consider targeted distribution of air purifiers to vulnerable populations during emergencies.

- Monitoring and evaluation: Implement routine monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to assess the long-term effectiveness of interventions. These should include air quality monitoring systems, clearly defined key performance indicators (KPIs). (6). Further research is needed on the cost-effectiveness of specific models and brands within the Thai context.

- Collaboration: Encourage cross-sector collaboration between the NHSO, Department of Local Administration, Ministry of Education, and Thai Health Promotion Foundation (ThaiHealth), and related partners to strengthen integrated policies and community-based initiatives that enhance child health, safety, and environmental well-being.

- Indoor air quality audits: Conduct regular indoor air quality (IAQ) audits in public buildings, including schools and child development centers, to identify pollution sources, assess ventilation using CO₂ as a proxy, log daily pollutant peaks, and map outdoor sources near windows, air intakes, and doors (28).

- Dedicated funding: Allocate long-term clean air grants or retrofitting budgets (e.g., Local Health Security Fund) for public buildings, with sustained funding for schools and child development centers, following successful models such as London’s school air quality program (6).

Funding Source

This research has received funding support from the Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) and the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF) via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources & Institutional Development, Research and Innovation [B41G680024].

Author

Dr. Wissawa Malakan

Researcher at Economic Environment Unit (E2U), HITAP

References:

- UNICEF. Estimated 13.6 million children in Thailand highly exposed to PM₂.₅. UNICEF. Bangkok: UNICEF Thailand.2025 [cited 2025 19 Oct]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/thailand/.

- Hfocus. Understanding “Clean Room”: An additional measure to support vulnerable groups affected by air pollution. Ministry of Public Health. 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.hfocus.org/content/2024/01/29639.

- Social Development Department. Indoor air quality management in 286 Bangkok’s early childhood development centers. Bangkok Metropolitan Administration; 2023.

- Navamindradhiraj University. Academic service project by College of Urban Development, Navamindradhiraj University 2023: Air quality monitoring at 20 BMA early childhood development centers, June–August 2023. Bangkok (Thailand): Navamindradhiraj University; 2023.

- Department of Health. Guidelines for establishing clean rooms in households, public buildings, and early childhood development centers. Nonthaburi (Thailand): Health Impact Assessment Division, Department of Health, Ministry of Public Health; 2024.

- Greater London Authority. The Mayor’s School Air Quality Audit Programme: Programme report. 2018.

- Supornpraditchai T. Demographic characteristics, individual self-protective behavior and health self-assessment among the people in areas with high PM 2.5 concentration in Bangkok. Acad J North Bangkok Univ. 2021;10(2), 107–124.

- SAWASDEE THAILAND. Thais Innovate! Showcasing the “Dust-Fighting Mosquito Net”: A Practical Solution to Help Reduce Air Pollution and Address PM 2.5 in Chiang Mai 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 9]. Available from: https://thailand.go.th.

- Department of Health. Department of Health advises educational institutions: Create dust-free rooms to reduce the impact of PM₂.₅ on children 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 12]. Available from: https://anamai.moph.go.th/th/news-anamai/43983.

- Attasuwan S. Air purifier business trends in Thailand 2024 [cited 2025 Aug 9]. Available from: https://www.thebusinessplus.com/air-purifier/.

- Committee on Labeling T. Announcement on the Classification of Products as Label-Controlled Goods. 2022.

- Thai Industrial Standards Institute. Specific criteria for inspection to grant approval for products in the electrical safety industry, for household and similar electrical appliances, Part 2(65): Particular requirements for air purifiers, Standard No. TIS 60335 Part 2(65)–2021. TISI; 2021.

- Ministry of Commerce. Royal Gazette declares that air purifier sellers must report price and quantity: Thai PBS; 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.thaipbs.or.th/news/content/352407.

- Sethasatsawat N. Factors affecting air purifier purchase decisions in Bangkok: Thammasat University; 2019.

- Hfocus. Smart Buy – testing center publishes air purifier performance, urging TISI to issue standards for consumer protection 2020 [cited 2025 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.hfocus.org/content/2020/01/18384.

- Foundation for Consumers. Smart Buy – Magazine reports second round of air purifier tests: many brands fail to reduce PM₂.₅ as advertised 2021 [cited 2025 July 3]. Available from: https://www.consumerthai.org.

- Matichon. Bangkok receives air quality monitors and installs dust-free classrooms to combat PM₂.₅ in schools 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 3]. Available from: https://www.matichon.co.th/local/quality-life/news_4938259.

- Department of Health. Medical and Public Health Operational Manual for Smog and PM2.5 Response: Ministry of Public Health, Thailand; 2025.

- U.S. EPA. Create a clean room to protect indoor air quality during a wildfire 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.epa.gov.

- U.S. EPA. Indoor Air Facts No. 4: Sick Building Syndrome (revised). Washington: U.S. EPA, Office of Air and Radiation; 1991.

- U.S. EPA. Air Pollution Control Technology Fact Sheet. Washington (DC): U.S. EPA, Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards; 2003.

- U.S. DOE. DOE-STD-3020-2015, Specification for HEPA Filters Used by DOE Contractors. Washington (DC): Office of Environment, Health, Safety & Security. 2015 [cited 2025 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.standards.doe.gov.

- U.S. EPA. Guide to Air Cleaners in the Home. Washington (DC): U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2018.

- Health Impact Assessment Division. How to choose an air purifier to fight PM₂.₅: Anamai Media; 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://multimedia.anamai.moph.go.th.

- Department of Health. Guidelines for choosing air purifiers and organizing a home to protect against PM₂.₅ 2025 [cited 2025 July 2]. Available from: https://anamai.moph.go.th.

- U.S. EPA. Consumer Messaging Guide for ENERGY STAR Certified Appliances. Washington (DC): U.S. EPA; 2017.

- U.S. EPA. Ozone Generators that are Sold as Air Cleaners 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 27]. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/.

- Greater London Authority. Toolkit of Measures to Improve Air Quality at Schools: The Mayor’s School Air Quality Audit Programme. London; 2018.

- Saravanakumar R, Selladurai V. Exergy analysis of a domestic refrigerator using eco-friendly R290/R600a refrigerant mixture as an alternative to R134a. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry. 2014;115(1):933-40.

- South Coast Air Quality Management District. Residential program offers free air purifiers for participating AB 617 communities: South Coast AQMD Advisor; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 23]. Available from: https://www.aqmd.gov/.